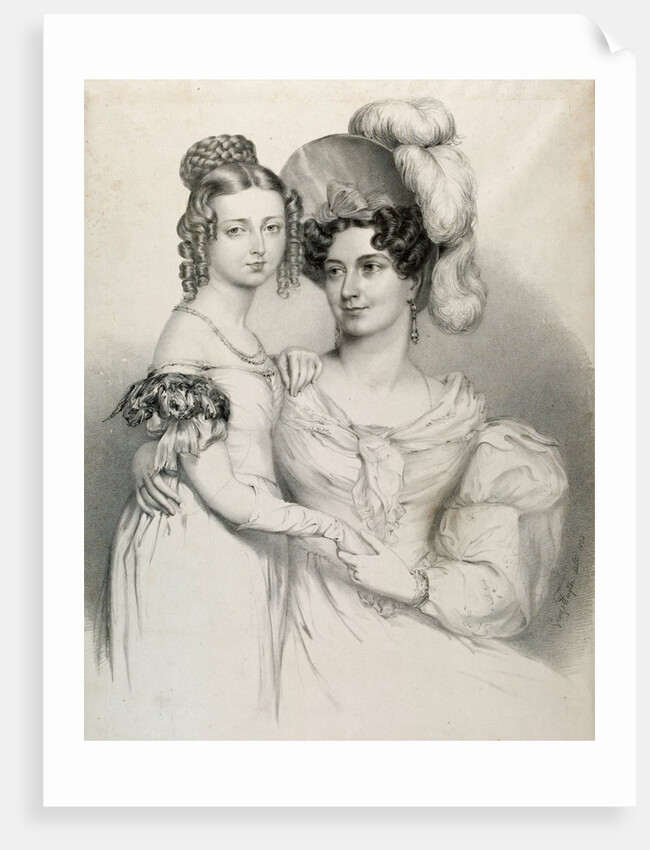

Victoria suffered from typhoid and why she was very sick, her mother and Sir John Conroy tried to make her sign a document making him secretary and her mother regent even after she is eighteen. Victoria refused.

In 1836 Victoria met Prince Albert de Saxe Coburg and Gotha, her future husband, (26 August 1819 – 14 December 1861) for the first time. The idea of marriage between Albert and his first cousin Victoria was first documented in an 1821 letter from his paternal grandmother, the Dowager Duchess of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld. By 1836, this idea had also arisen in the mind of their ambitious uncle Leopold, who had been King of the Belgians since 1831. Leopold arranged for his sister, Victoria's mother, to invite the Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and his two sons to visit her in May 1836, with the purpose of meeting Victoria.

On June 20 1837 King William IV died.

As the King had no legitimate children to succeeded, Victoria became Queen of England. At 6am on 20 June 1837, Victoria was woken at Kensington Palace to be told visitors had arrived with important news, which she later described in her diary: ‘I got out of bed and went into my sitting-room (only in my dressing-gown), and alone, and saw them. Lord Conyngham (the Lord Chamberlain) then acquainted me that my poor Uncle, the King, was no more, and had expired at 12 minutes p.2 this morning, and consequently that I am Queen.’

Victoria as a Queen became attached to the Prime Minister, William Lamb, Lord Melbourne, and trusted his opinions greatly. Henry William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne (15 March 1779 – 24 November 1848) was a British Whig politician who served as the Home Secretary and twice as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He is best known for helping Victoria settle into her role as Queen, acting almost as her private secretary.

Victoria appointed Harriet Leveson Gower, Duchess of Sutherland as her Mistress of the Robes. Harriet Elizabeth Georgiana Sutherland-Leveson-Gower, Duchess of Sutherland (née Howard; 21 May 1806 – 27 October 1868) was an English courtier and abolitionist from the Howard family. She was Mistress of the Robes under several Whig administrations: 1837–1841, 1846–1852, 1853–1858, and 1859–1861; and a great friend of Queen Victoria. She was an important figure in London's high society, and used her social position to undertake various philanthropic undertakings including the protest of the English ladies against American slavery.

The queen chose Marianne Skerrett as her Head Dresser. Marianne Skerrett (20 June 1793 – 29 July 1887) was a British courtier. She was a Dresser (lady's maid) to Queen Victoria between 1837 and 1862. She was responsible for the organization of the queen's chamber staff, handling the contacts with tradespeople and artists, making orders and paying them and answering begging letters.

As soon as Victoria ascended to the throne, she dismissed John Conroy from court. Conroy was immediately expelled from Victoria's household, though he remained in the Duchess of Kent's service for several more years. Given a pension and a baronetcy, Conroy retired to his estate near Reading, Berkshire, in 1842 and died heavily in debt twelve years later.

Victoria was crowned on June 28, 1838. The ceremony was held in Westminster Abbey after a public procession through the streets from Buckingham Palace, to which the Queen returned later as part of a second procession.

In 1839 Victoria got involved in some scandal when her mother's maid of honour, Flora Hastings, was said to be pregnant. The woman was actually dying of cancer. Lady Flora Elizabeth Rawdon-Hastings (11 February 1806 – 5 July 1839) was a British aristocrat and lady-in-waiting to Queen Victoria's mother. Her death in 1839 was the subject of a court scandal that gave the Queen a negative image. Sometime in 1839, Lady Flora began to experience pain and swelling in her lower abdomen. She visited the queen's physician, Sir James Clark, who could not diagnose her condition without an examination, which she refused. Clark assumed the abdominal growth was pregnancy, and met with Lady Flora twice a week from 10 January to 16 February. Her enemies, Baroness Lehzen and the Marchioness of Tavistock spread the rumour that she was "with child", and eventually Lehzen told Melbourne about her fears. On 2 February, the queen wrote in her journal that she suspected Conroy, a man whom she loathed intensely, to be the father, due to his taking a late-night carriage ride alone with Lady Flora. Lady Flora felt that she had to defend herself in public, publishing her version of events in the form of a letter which appeared in The Examiner, and blaming "a certain foreign lady" (Lehzen) for spreading the rumours. The accusations were proven false when Lady Flora finally consented to a physical examination by the royal doctors, who confirmed that she was not pregnant. She did, however, have an advanced cancerous liver tumour. Queen Victoria visited the now emaciated and clearly dying Lady Flora on 27 June.

The book also mentios the Bedchamber Crisis. The Bedchamber crisis was a constitutional crisis that occurred in the United Kingdom between 1839 and 1841. It began after Whig politician William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne declared his intention to resign as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom after a government bill passed by a very narrow margin of only five votes in the House of Commons. The crisis occurred very early in the reign of Queen Victoria and involved her first change of government. She was partial to Melbourne, and resisted the requests of his rival Robert Peel to replace some of her ladies-in-waiting, who were primarily from Whig-aligned families, with Conservative substitutes as a condition for forming a government. Following a few false moves toward an alternative Conservative prime minister and government, Melbourne was reinstated until the 1841 election, after which Peel was appointed Prime Minister and Victoria conceded to the replacement of six of her ladies-in-waiting.

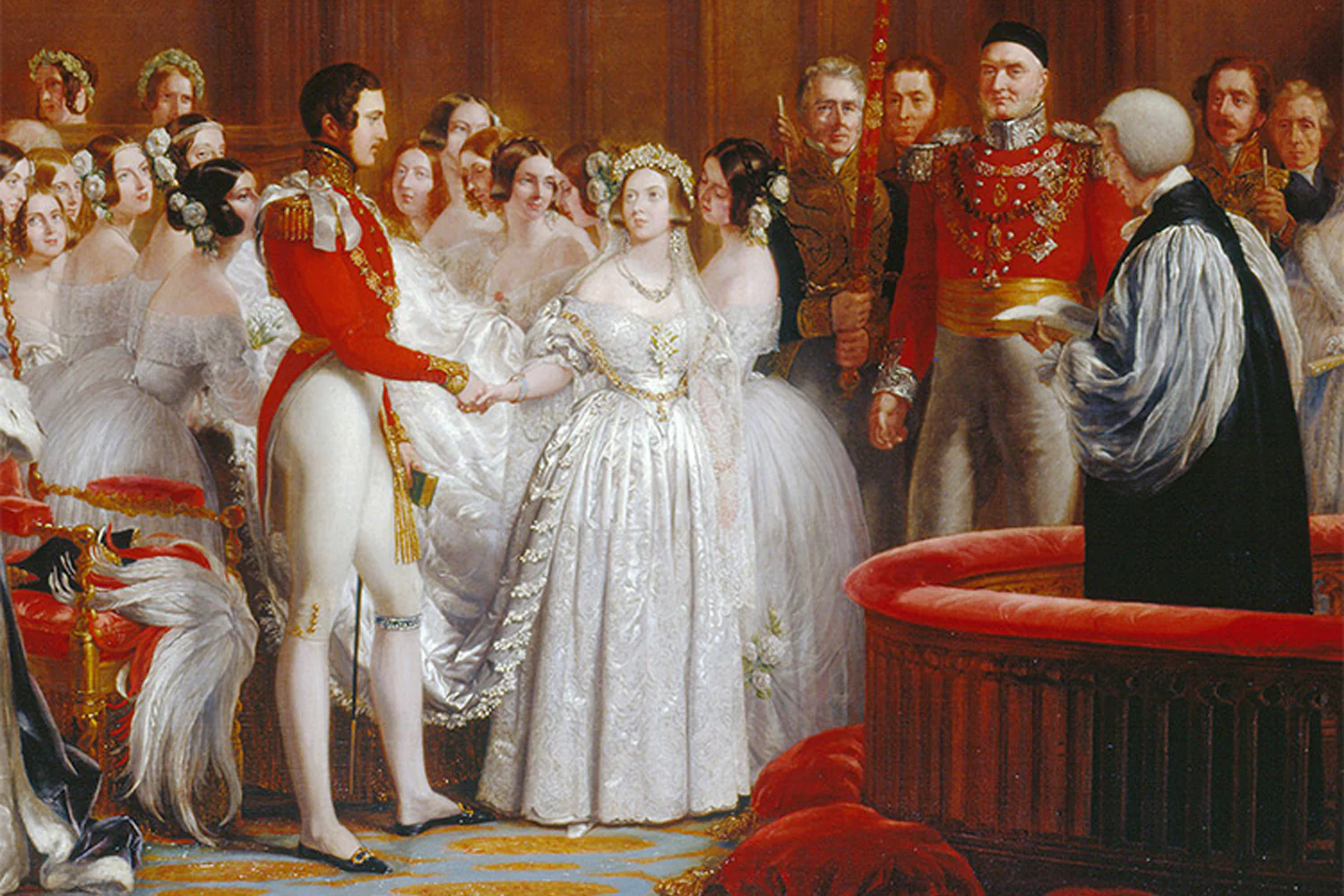

Victoria married Albert in 1840. The wedding of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom and Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha took place on 10 February 1840 at Chapel Royal, St James's Palace, in London.

Victoria and Albert had nine children: Victoria, Albert Edward, Alice, Alfred, Helena, Louise, Arthur, Leopold and Beatrice.

In 1851 the Great Exhibition was a big event in England. The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, also known as the Great Exhibition was an international exhibition that took place in Hyde Park, London, from 1 May to 15 October 1851. The event was organised by Henry Cole and Prince Albert.

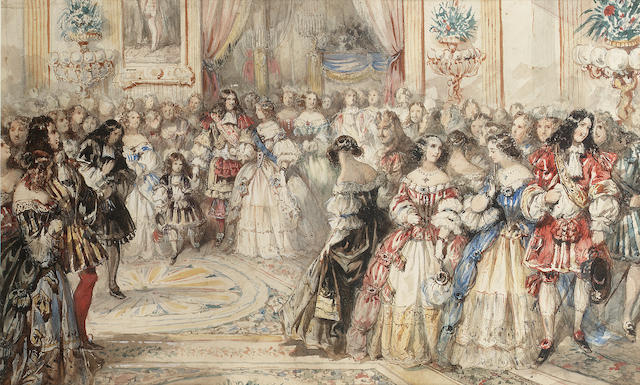

Another ball was the Plantagenet ball in 1842. The Plantagenet Ball was the first of three magnificent costume balls held by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert at Buckingham Palace. It took place on 12 May 1842 and was attended by over 2,000 people. Prince Albert dressed as Edward III, and Queen Victoria dressed as Edward's consort Queen Philippa of Hainault.Another one was the Powdered Ball in 1845. On 6th June 1845, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert hosted a Georgian themed ball at Buckingham Palace. It was an event where participants appeared in costume ranging from a ten-year period between 1740 and 1750.

Victoria visited France in 1855, a visit hosted by King Napoleon III and Empress Eugenie de Montijo. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were accompanied by the Prince of Wales and the Princess Royal as they made a historic State Visit to France, where they were hosted by Emperor Napoleon III and Empress Eugenie of France for a 10-day State Visit, which ended on this day in 1855.

Vicky, Princess Royal, married Frederick, the Crown Prince of Prussia. Queen Victoria was concerned that the Prussian prince would not find her daughter sufficiently attractive. Nevertheless, from the first dinner with the prince it was clear to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert that the mutual liking of the two young people that had begun in 1851 was still vivid. In fact, after only three days with the royal family Frederick asked Victoria's parents permission to marry their daughter. They were thrilled by the news but gave their approval on condition that the marriage should not take place before Victoria's 17th birthday. Once this condition was accepted the engagement of Victoria and Frederick was publicly announced on 17 May 1856.

Queen Victoria's mother, the Duchess of Kent died in 1861. The Duchess died at 09:30 on 16 March 1861, aged 74 years, with her daughter Victoria at her side. The Queen was much affected by her mother's death. Through reading her mother's papers, Victoria discovered that her mother had loved her deeply; she was heart-broken, and blamed Conroy and Lehzen for "wickedly" estranging her from her mother.

In December 1861 Prince Albert died. On 9 December, one of Albert's doctors diagnosed him with typhoid fever. Albert died at 10:50 p.m. on 14 December 1861 in the Blue Room at Windsor Castle, in the presence of the Queen and five of their nine children. The Queen's grief was overwhelming, and the tepid feelings that the public had for Albert were replaced by sympathy. The widowed Victoria never recovered from Albert's death; she entered into a deep state of mourning and wore black for the rest of her life.

In 1863 Bertie married Princess Alexandra of Denmark. The wedding of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII), and Princess Alexandra of Denmark took place on 10 March 1863 at St. George's Chapel, Windsor Castle. It was the first royal wedding to take place at St. George's.

After Albert's death the Queen put her trust in John Brown, her Highland Outdoor attendant, and there were rumours that they had a relationship. John Brown (8 December 1826 – 27 March 1883) was a Scottish personal attendant and favourite of Queen Victoria for many years after working as a ghillie for Prince Albert. He was appreciated by many (including the Queen) for his competence and companionship, and resented by others (most notably her son and heir apparent, the future Edward VII, the rest of the Queen's children, ministers, and the palace staff) for his influence and informal manner. The exact nature of his relationship with Victoria was the subject of great speculation by contemporaries.

No comments:

Post a Comment